Käthe Kollwitz, Tower of Mothers 1937. Germany. Depicting mothers standing in a circle to protect their children from the horrors of war

On February 22, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, “I would like to emphasise again that Ukraine is not just a neighbouring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space. These are our comrades, those dearest to us – not only colleagues, friends and people who once served together, but also relatives, people bound by blood, by family ties.”

Two days later, Russia invaded Ukraine. Ukraine has been an independent state for 31 years.

According to the U.N. High Commission for Human Rights, Russia has destroyed over 1500 civilian structures in Ukraine in the first 29 days. 953 civilians have been killed, including 78 children. According to the New York Times, Putin’s military has destroyed 23 hospitals, 330 schools, and 900 houses and apartment buildings. Russians destoyed a maternity hospital and a theater that provided refuge to 1500 women and children.

One in every two Ukrainian children has been displaced since Russia began its invasion on February 24th, according to the UN Children's Fund. Putin’s aggression has forced nearly 4 million refugees out of the country. That is 10% of the population of 44 million. Nearly all of these refugees are women and children, as the men have stayed behind to defend their homeland.

This is how Putin treats “those dearest to us.”

This is not the first time that both men and women had to take up arms to fight Russians to protect Ukraine and their families. And sadly, it is not the first time Ukrainians were separated from their children because of the cruelty of their Russian neighbor.

In the face of oppression and violence, Ukraine has produced some very important heroes who resisted Russian aggression.

In 2004, I interviewed a number of these heroes. Sadly, we have lost many. Some were murdered, others have died of old age. But, they left a legacy of dissent.

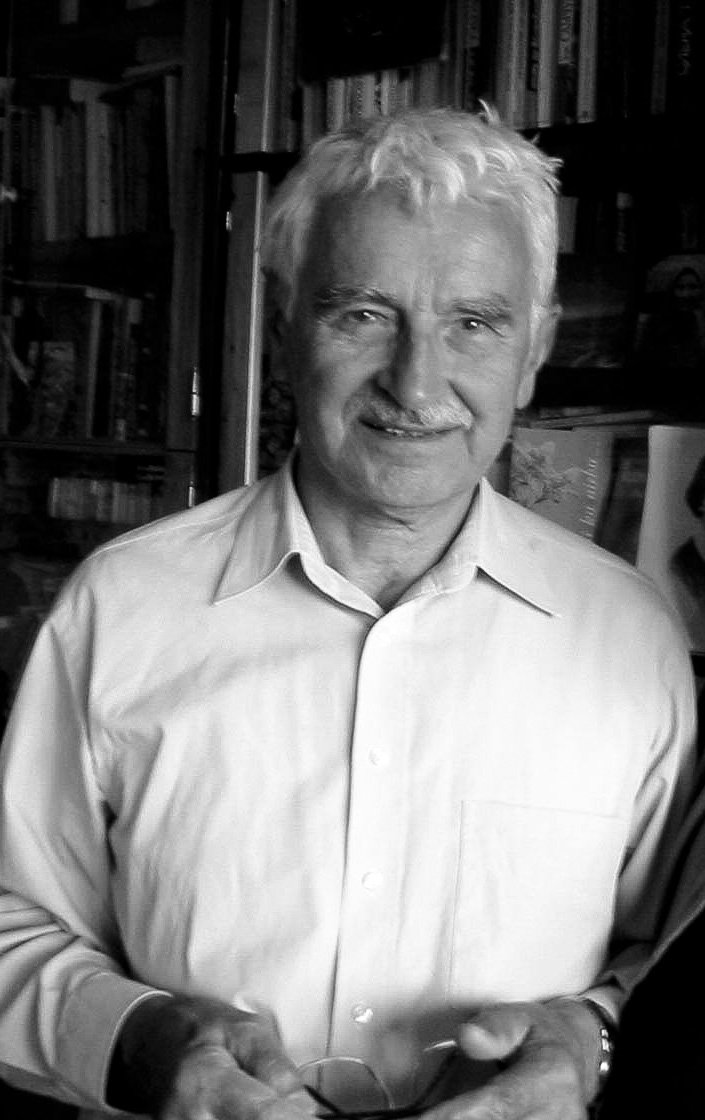

Yevhen Sverstyuk

Kyiv. 2004.

The handsome white haired man invited us to have tea. хочете чаю, would you like tea? Yevhen’s wife came into the room, a little old lady carrying a large tray. She quietly served us tea in graceful China cups and offered us some warm biscuits. Yevhen offered us a liqueur that his wife made. “I call this Lila, after my wife. It is made from nuts, 5 kinds of herbs and 5 kinds of berries. It is her specialty,” Yevhen said.

Yevhen was a kindly man whose erudition and wisdom were palpable. During our last interview I asked, “Can I come and study with you? I could learn so much from you. About philosophy and history.” Yevhen laughed, “We might have some problems, don’t you think? Since I speak Ukrainian and you English. And wouldn’t you have a long commute from the United States?”

Yevhen died in 2014 after Russian occupation of Crimea and Donbas. Before his death at 86 he spoke of the “huge social test of strength” that Ukraine was going through. “Both the struggle with the authoritarian regime and the victory of the Maidan revolution are imbued with the long familiar historical set up of foreign intervention. All of this is logical and one of the classic turns of history which is a test for all peoples in our Europe. All of that together makes for an incredibly responsible test for the freedom and independence of Ukrainians which needs to be passed through with dignity. “

All values are still true

“The world will be reborn when new people are willing to accept the torch. It often happens in history. The cycles come and go.”

Mbfitzmahan. Yevhen Sverstyuk. 2004. Kyiv, Ukraine.

It was a great honor to spend some hours with Yevhen Sverstyuk. Shauna and I met with him three times. He was a leading Ukrainian writer, thinker, and moral leader who defied Soviet occupation and suppression.

In 1972, the Soviet government arrested him during Brezhnev’s campaign to remove dangerous Ukrainian intellectuals.

Yevhen had pushed the limits of the government since 1952. Many of his writings were disseminated in secret. The last straw was when he wrote an essay and he failed to cite Karl Marx or Lenin. “I wrote my essay as though those thinkers did not exist. My essay was seen by the prosecutor as a rejection of Soviet ideology. The KGB felt that this was hostile, but they could not say it was anti-Soviet. It was on the razor edge. I was indicted not only for what I wrote, but also because who I was. The authorities thought the book could have a bad influence, but they feared my influence more.”

I believe that Yevhen was being modest, perhaps careful. His essay speaks of the unspeakable. He looks at Ukraine as a nation separate from Russia. He writes "nationalism is a necessary stage of universal progress; the demise of a nation is as tragic for that nation as it is for the whole of mankind." (Sverstyuk Ivhen. (1976). Clandestine essays. Published by the Ukrainian Academic Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.)

Yevhen Sverstyuk was sentenced to spend 12 years in Soviet labor camps, separated from his wife and little children.

Yevhen said, “not many talk about the pain caused to families.”

“My wife is a very gentle person. She would come to see me in the concentration camp. Once she came all the way to Siberia and then was not allowed to see me. She could come only once a year. It was a very long and hard journey and she was extremely disappointed that she could not see me. Later, when I finally got to see my daughter, Veera, when she was 13 and she came to visit me in jail, she did not understand. She said, “Daddy, why is that solder here?” She saw the guard walking outside my window. It was very hard to get to know her. It was typical at that time for children not to recognize their fathers after years of incarceration. During their father’s absence, children of political prisoners had to explain where their fathers were. Some people knew where I was and others didn’t. Teachers did not ask my daughter where her father was, only the children asked her. But, she was very embarrassed.

When I got back home after all those years, one teacher gave me a written composition my son had written. He was asked to write about his number one role model, and he wrote, “My father.” The teacher knew my story and hid his paper and showed it to no one until I came home. She was afraid that the authorities would find it and my son would get in trouble. My son was older and was proud of me, but he never demonstrated his feelings. He was quiet. He was only 12 when I went to prison.

Some wives joined their husbands in exile. That was allowed only in cases where the husband was sick or the when the husband could not adjust to life by himself. For example, there is a philosopher, Vasyl Lisovy. He was in exile in eastern Siberia and his wife and two children moved there with him. I didn’t want my wife to have to live in exile with me, even if she wanted to. I was in eastern Siberia where it is a land of eternal ice. I was in camp #36.

When I came home, though, my wife and I were just as close as when I left. Just happy to be back together. And, as you see, we are still happy to be back together.”

Presciently, he said,

”Today many people live under the illusion that the world has changed to the extent that the old truths have no more value. This is a big mistake. All true values are still true. Until there are people who can carry these values, there will not be much change in the world. There will be new generations that will not carry or accept the torch from the last generations. Life then will decay. The world will be reborn when new people are willing to accept the torch. It often happens in history. The cycles come and go.”